How ‘Ray’ introduces the Master’s work to an entirely new generation.

It’s not about what you see, it’s about what you take back. ‘Ray’, through its 4 films does prod you enough to make you sit up and take notice.

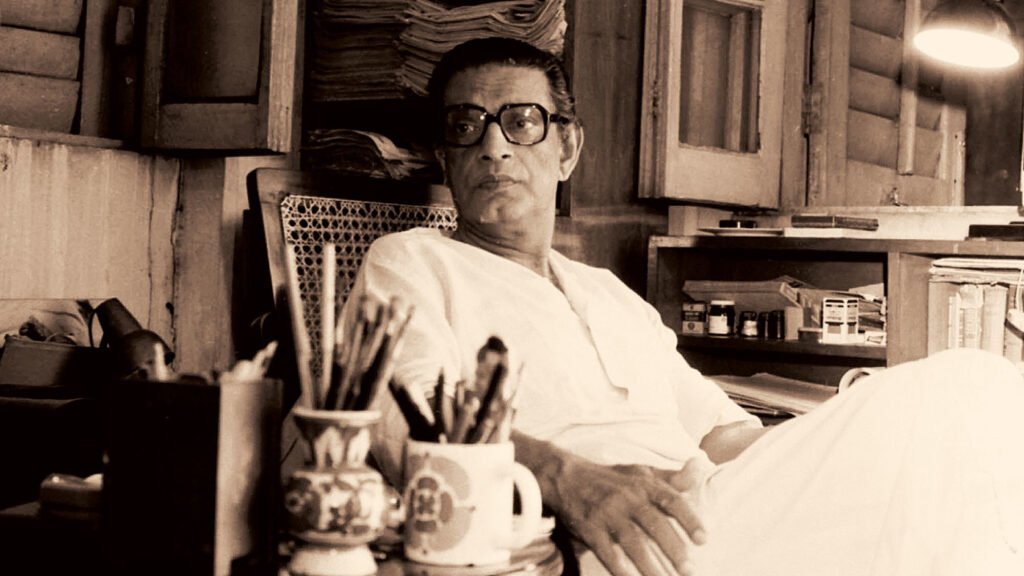

‘Cinema’s characteristic forte is its ability to capture and communicate the intimacies of the human mind.’

– Satyajit Ray

For someone who has devoured cinema for over a decade, it may come as a surprise that I have yet to watch Satyajit Ray’s work. But I have come to realise that there’s a time and place for everything. I’ve been meaning to dive headfirst into the world of the master filmmaker – who was also a gifted composer, calligrapher, writer, graphic designer – and experience the raw, visceral, and unapologetic cinematic gaze with which Ray conquered the world – influencing the industry and its cohorts till today.

Although his films have eluded me for quite a while, sometimes all it takes is a trigger.

Not only has the Netflix anthology compelled me to watch his feature films but has also led me down a path which branches and reaches out – twisting and swirling, eventually coalescing to form an interconnected web; a constellation of sorts highlighting the beauty in connections. This introduction acts as a magical portal to the wonderful and compelling world of Ray – to me, as well as to an entirely new generation of viewers.

The four films in the series – criticised and lambasted by certain reviewers, which I shall talk more about, going forward – do a commendable job at enthralling the viewer and taking them through a whimsical, astonishing, mystical, provocative, and metaphorical journey – across time, both literally and metaphorically.

This emphasis on ‘the journey’ is ever present – the transformation of the self, the exploration of the capacities of the mind, the dichotomous nature of life, the human condition – simple tropes that revolve around greed, power, acceptance, and contentment.

Being adaptations of Ray’s work, the filmmakers, naturally, felt inclined to pay homage to the Master. The four episodes are Meta in a way, not only by how they seem to reference the director and his work but also, in essence, are films about artists, the industry and cinematic styles – the first episode isn’t as explicit but is a nod towards a certain narrative technique where what is shown to the viewer may not necessarily be true.

Each part has its own quirks – with positives and negatives – but in the larger scheme of things, ‘Ray’ commands attention.

In part one, Ali Fazal shines and takes centre stage – from his meteoric rise to his cataclysmic fall into the abyss. Martin Scorsese often talks about how Ray has influenced his work. With ‘Forget Me Not’ shades of Shutter Island are ever present.

In ‘Bahrupiya’, Kay Kay Menon is delightful and unnerving. Be careful of what you wish for as this dark and twisted adaptation plays out like a speculative fiction film infused with the mystical – which reminded me a bit of Ted Chiang’s The Tower of Babylon and Seventy-Two Letters.

Part three – the Manoj Bajpayee starrer – exults in camera work influenced by Wes Anderson’s whimsical takes (who co-incidentally also has been influenced by Ray and his work). ‘Hungama Hai Kyon Barpa’ is beautifully executed as it flits from being a cinematic experience, to a dream, to being a theatrical performance – carefully crafted with a spellbinding narrative that pays homage to artists and performers.

‘Spotlight’ explores Ray’s disdain for dogmatism with religious and political undertones all the while highlighting the fickle and transient nature of our state of being.

The Netflix anthology has effectively opened a pandora’s box, setting the stage for more adaptations – accentuating Ray’s range and ability to conjure up tales that startle and delight. My favourite out of the four, you ask? It does not matter. My opinion at this juncture will only colour your own sense of judgement. And that is exactly why some things just need to be left alone in the world.

For those deriding the Netflix series, I urge them to not be myopic in their over-enthusiastic frenzy of dismissing the anthology as a hollow, commercial rendition.

While you may ridicule the processes and techniques adopted you cannot compare them to Satyajit Ray’s style or what could have been done. Comparison – while normal and obvious, in this case, is bordering on the criminal – each film stands on its own two feet and this is where reviews start to annoy.

Sometimes we as critics (and I include myself here as well) lack the humility to see beyond our own noses and ultimately judge content from a lens that is biased – spurning potential viewers from gems that are diamonds in the rough.

The purpose of a review is to objectively critique a piece of work. But in the end what are we being critical of? The structure? The Narrative? The Style? The Acting? The Camerawork? These seem superficial if we fail to look beyond the visual. It’s not about what you see, it’s about what you take back and ‘Ray’, through its 4 films does prod you enough to make you sit up and take notice.

We live in an age where algorithms are tailored to our tastes and in some cases push content that you are forced to consume. YouTube does that with movie/tv trailers for me and while I do get sucked in, I also do make it a point to abstain – case in point – Ray.

Hence, the lack of a trailer here.

‘Ray’ will be seen as a deeply polarising collective that while taken in negative sense could be a blessing in disguise. As much as I hate to say it, in our fast-paced world, to be polarising is to be relevant.

The process of writing this piece has been extremely enjoyable, introspective, and bordering on the therapeutic. Sometimes we try to impress our own thoughts and perspectives and thrust them onto the world. It’s time to be more mindful and in the words of Satyajit Ray – “There’s always some room for improvisation.”

My journey continues with The Apu Trilogy + Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye by Andrew Robinson + Satyajit Ray | A Documentary by Shyam Benegal

Additional Resources

Shyam Benegal on Satyajit Ray

On how Satyajit Ray influenced him and his work:

Shyam Benegal Interviewing Satyajit Ray “An Art Of Film”

Listen to Satyajit Ray talk more about his process: